Communism in Eastern Europe

A Historical Journey Through Ideology, Implementation, and Legacy

Communism in Eastern Europe represents one of the most transformative and controversial chapters of the 20th century. From the rise of Soviet influence after World War II to the dramatic collapse of communist regimes in 1989–1991, the region’s experience with communism shaped its political, economic, social, and cultural landscapes. This blog delves into the origins, implementation, challenges, and lasting legacy of communism in Eastern Europe, focusing on key countries like Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania, and Yugoslavia, while exploring its broader implications.

The Origins of

Communism in

Eastern Europe

Eastern Bloc

Communism, rooted in the theories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, envisioned a classless, stateless society where the means of production are collectively owned. In Eastern Europe, communism gained traction after the Russian Revolution of 1917, when the Bolsheviks established the Soviet Union as a model for socialist governance. However, its widespread adoption in the region was largely a post-World War II phenomenon, driven by geopolitical shifts and Soviet dominance.

Key Factors Leading to Communism’s Rise:

1950 Soviet Stamp

Post-War Power Vacuum

World War II left Eastern Europe devastated, with weakened economies, destroyed infrastructure, and political instability. The defeat of Nazi Germany created opportunities for new ideologies to fill the void.

The Yalta and Potsdam Conferences (1945) divided Europe into spheres of influence, placing Eastern Europe under Soviet control, paving the way for communist regimes.

Soviet Influence and Liberation

The Red Army’s liberation of Eastern Europe from Nazi occupation positioned the Soviet Union as a dominant force. Countries like Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia saw Soviet-backed communist parties rise to power.

The Cominform (1947), a Soviet-led organization, coordinated communist parties across the region to align with Moscow’s agenda.

Local Communist Movements

Indigenous communist parties, though often small before the war, gained legitimacy by participating in anti-fascist resistance movements. In Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito’s Partisans played a significant role in liberating the country, giving communism a nationalist appeal.

Economic inequality, feudal remnants, and dissatisfaction with pre-war governments made communism’s promise of equality and modernization attractive to workers, peasants, and intellectuals.

Implementation of

Communism in

Eastern Europe

Eastern Countries of Europe

Between 1945 and 1948, communist regimes were established across Eastern Europe, often through a combination of elections, coalitions, and Soviet-backed coups. Countries like Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania became part of the Soviet Bloc, while Yugoslavia pursued a non-aligned path. The implementation of communism varied by country but followed a general pattern inspired by the Soviet model.

Key Features of Communist Governance:

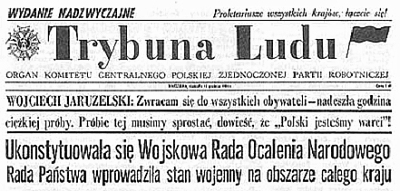

Martial Law in Poland in 1981

Political Structure

One-Party Rule: Communist parties monopolized power, suppressing opposition and establishing single-party states. For example, the Polish United Workers’ Party and the Socialist Unity Party in East Germany dominated political life.

Centralized Control: Governments were highly centralized, with decisions made by party elites loyal to Moscow (except in Yugoslavia). Dissent was met with censorship, surveillance, and repression by secret police (e.g., Stasi in East Germany, Securitate in Romania).

Cult of Personality: Leaders like Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu and East Germany’s Walter Ulbricht were glorified as infallible figures.

Economic System

Planned Economy: Central planning replaced market mechanisms, with state ownership of industries, agriculture, and resources. Five-year plans set production targets, prioritizing heavy industry and collectivization.

Collectivization: Agricultural land was seized from private owners and organized into collective farms, often met with resistance from peasants, as seen in Hungary and Poland.

Industrialization: Rapid industrialization aimed to modernize economies, achieving some successes (e.g., East Germany’s industrial output) but often at the cost of consumer goods shortages.

Social Policies

Education and Welfare: Communist regimes expanded access to education, healthcare, and housing, reducing illiteracy and improving living standards in some areas. For example, Czechoslovakia’s literacy rate reached nearly 100% by the 1960s.

Gender Equality: Women were encouraged to join the workforce, and policies promoted gender parity, though leadership roles remained male-dominated.

Propaganda and Culture: Art, literature, and media were controlled to promote socialist values, stifling creative freedom. Socialist realism became the dominant artistic style.

Foreign Policy Alignment: Most Eastern European countries joined the Warsaw Pact (1955), a military alliance led by the Soviet Union, and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) to coordinate economic policies.

Yugoslavia, under Tito, broke with Moscow in 1948, pursuing a non-aligned, market-oriented socialism, making it an outlier in the region.

Successes of Communism in Eastern Europe

Countries which once had overtly Marxist–Leninist governments in bright red and countries the USSR considered at one point to be "moving toward socialism" in orange

Despite its challenges, communism achieved notable successes in certain areas:

Industrial Growth: Countries like East Germany and Czechoslovakia became industrial powerhouses within the Soviet Bloc, with significant increases in steel, machinery, and chemical production.

Social Mobility: Expanded education and job opportunities allowed workers and peasants to access professions previously reserved for elites.

Infrastructure Development: Massive investments in housing, roads, and public transport improved urban landscapes, particularly in Poland and Hungary.

Social Welfare: Universal healthcare, free education, and subsidized housing reduced poverty and inequality in many countries, though quality varied.

Women’s Empowerment: Workforce participation for women increased significantly, with countries like East Germany achieving near gender parity in employment by the 1980s.

Challenges and Failures

Countries in Cold war in 1980

Communism in Eastern Europe faced persistent challenges that eroded its legitimacy and led to widespread discontent:

Economic Stagnation

Central planning was inefficient, leading to shortages of consumer goods, long queues, and black markets. By the 1970s, countries like Poland faced chronic food shortages.

Lack of innovation and competition stifled technological progress, leaving Eastern Europe lagging behind the West.

Heavy reliance on Soviet subsidies (e.g., cheap oil) made economies vulnerable to external shocks.

Political Repression

Dissent was brutally suppressed, with political prisoners, show trials, and purges. The 1956 Hungarian Uprising and the 1968 Prague Spring were crushed by Soviet forces, exposing the limits of reform.

Surveillance by secret police created a climate of fear, undermining trust in institutions.

Censorship alienated intellectuals and artists, many of whom defected to the West.

Social Discontent

Promises of equality were undermined by privileges for party elites, fostering resentment among ordinary citizens.

Collectivization disrupted rural communities, leading to resistance and declining agricultural output in countries like Romania.

Ethnic tensions persisted, as centralized policies often ignored regional identities, particularly in Yugoslavia.

International Isolation

Alignment with the Soviet Union isolated Eastern Europe from Western markets and innovations, deepening economic disparities.

The Iron Curtain symbolized the region’s division, limiting cultural and intellectual exchange.

Environmental Degradation

Rapid industrialization prioritized output over sustainability, causing severe pollution. For example, East Germany’s lignite mining led to air and water contamination, contributing to health issues.

Resistance and Reform Movements

Throughout the communist era, Eastern Europe saw waves of resistance and attempts at reform:

1956 Hungarian Uprising: A nationwide revolt against Soviet control was crushed, but it inspired future dissent.

1968 Prague Spring: Czechoslovakia’s attempt to create “socialism with a human face” under Alexander Dubček was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops, highlighting the Soviet Union’s intolerance for deviation.

Solidarity Movement in Poland: Founded in 1980, the Solidarity trade union, led by Lech Wałęsa, challenged communist rule through strikes and negotiations, becoming a catalyst for change.

Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia: A human rights manifesto by intellectuals like Václav Havel demanded political freedoms, influencing later revolutions.

These movements, combined with economic decline and Gorbachev’s reforms in the Soviet Union (glasnost and perestroika), set the stage for communism’s collapse.

The Fall of Communism (1989–1991)

Changes in national boundaries after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc

The late 1980s marked a turning point, as economic crises, public discontent, and weakening Soviet control culminated in the fall of communist regimes:

Poland: Roundtable talks in 1989 led to semi-free elections, with Solidarity winning a landslide, ending communist rule.

Hungary: The opening of its border with Austria in 1989 symbolized the Iron Curtain’s collapse, followed by multi-party elections in 1990.

East Germany: Mass protests and the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 led to German reunification in 1990.

Czechoslovakia: The Velvet Revolution in 1989, led by peaceful protests, ended communist rule without bloodshed.

Romania: A violent revolution in December 1989 overthrew Ceaușescu, who was executed, marking a bloody transition.

Yugoslavia: Ethnic tensions and economic decline led to its dissolution in the early 1990s, followed by civil wars.

Albania and Bulgaria: These countries transitioned more gradually, with communist regimes collapsing by 1991.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the definitive end of the communist era in Eastern Europe.

Legacy of Communism in Eastern Europe

The legacy of communism in Eastern Europe is complex, with enduring impacts on politics, economies, societies, and identities:

Political Transformation

Most countries transitioned to liberal democracies, joining the European Union (e.g., Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic in 2004) and NATO.

However, authoritarian tendencies persist in some areas, with leaders exploiting nostalgia for communist-era stability.

Economic Challenges

The shift to market economies was painful, with unemployment, inequality, and privatization scandals in the 1990s. Countries like Poland and the Czech Republic recovered faster, while Romania and Bulgaria lagged.

Infrastructure and industrial bases built under communism provided a foundation for growth, but environmental damage required costly remediation.

Social and Cultural Impacts

Communist-era education and welfare systems left a legacy of high literacy and skilled workforces, benefiting post-communist economies.

Nostalgia for communism (“Ostalgie” in East Germany) persists among some who miss social security, though younger generations embrace Western values.

Cultural suppression under communism spurred vibrant post-1989 artistic and intellectual movements.

Regional Disparities

The dissolution of Yugoslavia led to devastating wars, leaving lasting ethnic tensions in the Balkans.

East Germany’s integration into a unified Germany highlighted economic disparities between former communist and capitalist regions.

Global Lessons

Eastern Europe’s experience underscored the challenges of implementing Marxist ideals in diverse contexts, highlighting issues of centralization and repression.

The region’s transition to democracy and capitalism remains a case study for post-authoritarian societies worldwide.

Conclusion

Communism in Eastern Europe was a bold experiment that promised equality and progress but often delivered repression, stagnation, and division. Its rise was fueled by post-war realities and Soviet ambition, while its fall reflected the resilience of human aspirations for freedom and prosperity. Today, the region stands as a testament to both the failures of centralized control and the enduring impact of its social achievements.

As Eastern Europe navigates its post-communist identity, the lessons of this era continue to shape global debates on governance, economics, and human rights.

Comments

Post a Comment